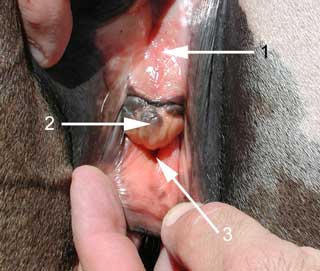

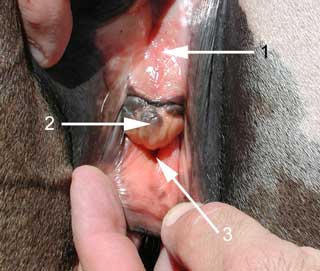

| This is a picture of a mareís

external genitalia. These are areas of focus when cleaning to prevent

the spread of CEM. 1) Beginning of the vaginal opening 2) Clitoris 3) Clitoral fossa or sinus |

Introduction: Contagious equine metritis (CEM) is a venereal disease that is spread from horse to horse most often through contact made during the breeding process. Both stallions and mares can be infected with the disease. Mares may become infected and carriers of the disease for several months or longer. Stallions carry the contagious equine metritis organism on their external genitalia, and may do so for years. Some reports indicate that newborn foals may become infected at birth. Because contagious equine metritis can be a serious problem, any suspected cases must be reported to regulatory authorities. Horses seem to be the only natural host for the disease, with thoroughbred horses, particularly in Europe, being more prone than other breeds.

Causative Agent: CEM is caused by two strains of a gram-negative bacteria called Taylorella equigenitalis. Taylorella equigenitalis can be found in the smegma of the prepuce and the surface of the penis in the stallion, especially in the urethral fossa.

Clinical Signs: In the mare, CEM causes metritis (inflammation of the uterus) and often a grayish vaginal discharge. The vaginal discharge will be noticed on the tail and inside the mare's thighs. It may be wet or already dry. Sometimes the sticky discharge will appear as soon as 2-6 days after breeding. The discharge usually appears about 10-14 days after the mare has been bred to an infected stallion. If this is the first time the mare has been infected, the mare will often "short-cycle" and a temporary period of infertility may result. The infection and discharge will often subside after a few days, but the mare may remain chronically infected for several months. During these months of infection, the mare may not show any clinical signs except for a decreased conception rate. However, after the infection subsides, fertility returns to normal for most mares. If infected mares do conceive, they may abort the fetus, or continue to carry the foal to term. These foals often become infected and many become chronic carriers of the Taylorella equigenitalis organism. Chronically infected mares and stallions do not show signs of infection or disease.

Disease Transmission: The disease is naturally transmitted during the mating process. However, it can be transmitted through the use of contaminated reproductive instruments and equipment. For example, equipment used for artificial insemination that is not properly sanitized between mares often spreads the disease. During the breeding season, an infected stallion may infect several mares before CEM is suspected and diagnosed.

Diagnosis: CEM is reported to be the most contagious bacterial venereal infection of horses. It should be suspected when several mares develop the clinical signs after having been bred to the same stallion. It should also be suspected anytime a mare has any sort of vaginal discharge. Although clinical signs may indicate CEM, laboratory tests are essential to confirm a case or outbreak.

In all stages of the disease, isolation of the Taylorella equigenitalis organism is essential for a precise diagnosis of CEM. However, isolation of Taylorella equigenitalis is sometimes difficult, and special care should be taken in the collection and transport of any samples. Serology may be used to identify CEM in mares, but it is of no use on infected stallions.

Mares suspected of being infected should be cultured during estrus, preferably during the first part of the heat cycle. Swabs should be gathered from the uterus, clitoral fossa, and clitoral sinuses of the mare. In the stallion, the cultures can be taken from the urethra, urethral fossa and diverticulum, and the sheath. Culture swabs should be placed immediately in transport media (Amies) and maintained at 4

0 C or lower while transporting it to the laboratory. If the time to the laboratory will be longer than 24 hours, the specimens should be frozen.When determining if a stallion is CEM free, at least three separate samples should be collected and tested before the stallion is declared free of CEM. Test-mating of suspected stallions to susceptible mares is sometimes also done. The mares that are bred by the suspect stallion are then tested for the presence of Taylorella equigenitalis.

Treatment: In the mare, treatment usually involves helping the mare clear the initial infection. Many of the mild cases of CEM will naturally be cleared by the mare in about 3 weeks. Other mares may benefit by receiving antibiotics to help treat uterine infections. These antibiotics will usually not completely clear the mare of the Taylorella equigenitalis organism, but will help eliminate the uterus infection and associated signs.

After the initial infection has been cleared, the external genitalia (vulva, clitoris, clitoral fossa or sinuses) of the mare can be cleaned with disinfectant and topical antibiotics. Current procedures include washing these areas with soap and water. After the washing, each area is scrubbed with chlorhexidine surgical scrub once a day for 5 days. The chlorhexidine scrub should have contact with each area for approximately 2 minutes. Because it may irritate the sensitive mucous membranes, all the chlorhexidine scrub must be rinsed away with warm water after the cleaning. After a thorough rinsing, a nitrofurazone-containing ointment should be placed over each area. This 5 day treatment must be used sparingly, because the prolonged use of chlorhexidine will destroy normal flora.

In mares, the clitoral sinuses are common sites for the Taylorella equigenitalis organism to remain. These areas are also difficult to expose for cleaning and treatment. Because of this, surgical removal of the clitoral sinuses may be necessary to rid the mare of infection.

|

|

A stallionís external genitalia (penis, sheath and prepuce) should also be treated in a similar fashion to the 5-day treatment described previously for mares. To thoroughly wash the penis and sheath, the stallion must be teased. The entire extended penis, with particular attention on the urethral fossa, should be cleaned. All smegma must be removed from the urethral fossa or urethral diverticulum (see page B760 for additional help on cleaning this area). After a thorough cleaning with chlorhexidine scrub and a good rinse, nitrofurazone-containing ointment should be applied. This procedure should be performed once a day for 5 days.

Prevention: Currently, vaccination is not practical nor recommended for preventing CEM. It is also important to realize that once infected, a mare naturally develops some immunity. This can be a problem, however, because each time the mare is exposed to CEM it increases the chances of her becoming a carrier for the disease. Since infections are not apparent in carrier mares and stallions, the disease is often very difficult to control.

The best way to prevent this problem is to have a thorough infectious disease prevention program in place. When focusing on CEM, special care should be taken to prevent potentially infectious mares or stallions from entering a breeding program. Potential carrier mares should be tested before being bred to stallions to prevent the spread of Taylorella equigenitalis. It is also essential that any mare or stallion suspected of being infected with an active form of CEM be identified and tested immediately. To help prevent CEM from becoming a serious problem in the United States, strict regulations apply when importing horses from overseas. For example, horses imported into the United States must be in the country of export for 60 days prior to exportation to the U.S. Otherwise, they must come with a certificate of health issued by a full-time salaried veterinary officer of the national government of each country in which the horse has been during the 60 days immediately preceding shipment. Other regulations may apply depending on the country and current circumstances, so it is recommended that state and federal veterinarians be involved early on when attempting to import a horse from another country.